10 Early Inventions That Led to the Modern Submarine

You might’ve heard of Narcís Monturiol’s Ictíneo—the ingenious pedal-powered submarine launched in mid-19th century Barcelona. It’s often celebrated as one of the earliest true submarines. But here’s the kicker: Monturiol didn’t invent the submarine. Not even close.

In fact, the idea of underwater travel dates back over 2,000 years. Way before steam engines and propellers, early inventors were already dreaming up wild ways to explore beneath the surface—sometimes using primitive air chambers, sometimes diving bells, and occasionally, entire underwater boats carved from wood or sealed with leather.

What’s even more mind-blowing? Some of these early attempts actually worked.

So if you thought submarines were a modern marvel, think again. From ancient Greek concepts to Renaissance-era machines, here are ten of the oldest underwater vessels and diving technologies, all created before 1800, ranked in reverse chronological order. These aren’t just historical curiosities—they’re proof that human curiosity has always pushed toward the impossible.

10. The Nautilus (1800): The Submarine That Tried to End All War

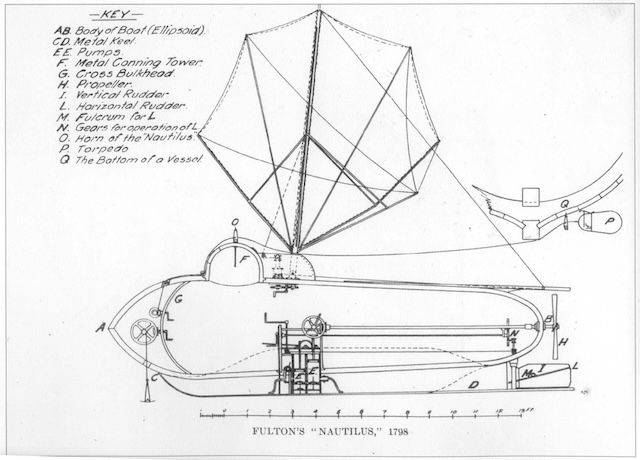

Before Jules Verne’s legendary Nautilus ever dived beneath the fictional seas, there was a very real prototype—Robert Fulton’s Nautilus, built in 1800 France. While Fulton would later rise to fame as the steamboat guy, he personally believed this strange copper-skinned vessel was his most revolutionary creation.

Designed with a collapsible wooden mast, hand-cranked propeller, and a sleek body that resembled a metallic fish, the Nautilus wasn’t just a feat of 19th-century engineering—it was a bold political statement. Fulton imagined a future where no navy could dominate the oceans, and submarines like his would be the ultimate equalizers in warfare. He even added a self-propelled bomb to prove it.

But here’s the twist: no one wanted it.

He pitched the idea to the French, then the British, and finally to the United States—each time facing rejection. One skeptical French admiral dismissed the Nautilus as “more suited to pirates or Algerians,” a jab at its unorthodox tactics rather than its capabilities.

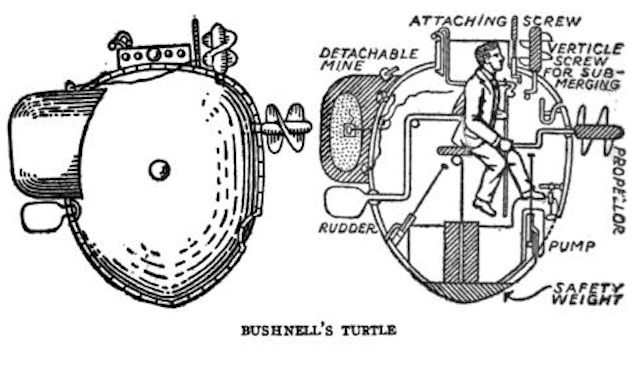

9. “Turtle”, 1776: The First Submarine in Combat

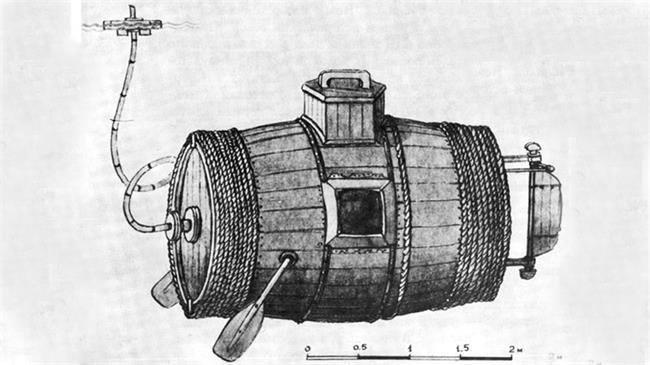

The story of the “Turtle” is one of ambition, innovation, and, ultimately, failure—but it’s a tale that marked a pivotal moment in naval history. In 1776, during the height of the American Revolutionary War, engineer David Bushnell unveiled the world’s first submarine, aptly named the “Turtle.” Its mission? To strike at the heart of the British fleet by attaching a time-delay mine to enemy ships. Unfortunately, the bold experiment ended in disappointment, as all three attempts to carry out this daring plan failed.

The “Turtle” itself was a far cry from the sleek, high-tech submarines we think of today. This pear-shaped vessel, measuring just 2.3 by 1.8 meters, was essentially a wooden barrel reinforced with iron bands. It was small—just large enough to fit one operator—and relied entirely on manual propulsion. The lone pilot would crank the propeller by hand, making it a slow and grueling process. Despite its simplicity, the “Turtle” represented a groundbreaking idea: the use of underwater technology in warfare.

A Bold Plan That Fell Short

The mission was as daring as it was risky. The operator would navigate the “Turtle” underwater, using a screw-like device to attach the mine to the hull of an enemy ship. However, the execution proved to be its downfall. Factors like strong tides, poor visibility, and mechanical challenges thwarted every attempt. While the “Turtle” never succeeded in its mission, it captured the imagination of its contemporaries and laid the groundwork for future innovations in underwater warfare.

The Mysterious Fate of David Bushnell

Following the failure of the “Turtle,” David Bushnell’s story takes an intriguing turn. Eleven years after the war, he seemingly vanished from public life. He moved to Georgia, changed his name to Bush, and began practicing medicine. Historians speculate that Bushnell wanted to distance himself from the stigma of the “Turtle’s” failure. Whether it was shame, frustration, or simply a desire for a fresh start, Bushnell’s decision to reinvent himself remains a fascinating chapter in the history of innovation.

Legacy of the “Turtle”

Although the “Turtle” was a failure in its time, its significance cannot be overstated. It was the first attempt to use a submarine in combat, proving that underwater vehicles could be more than just a concept. The lessons learned from the “Turtle” paved the way for future advancements, ultimately leading to the sophisticated submarines we see today.

The story of the “Turtle” is a reminder that innovation often comes with setbacks. Even the most ambitious ideas can falter, but their impact can ripple through history, inspiring future generations to keep pushing the boundaries of what’s possible.

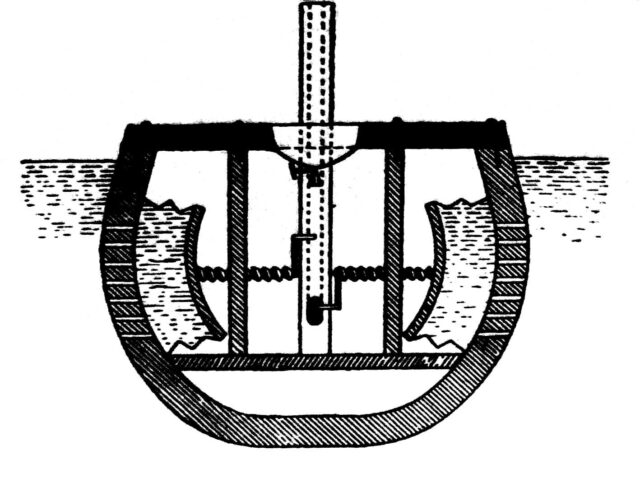

8. The 1775 Diving Bell Upgrade That Cost Its Inventor His Life

By the late 1700s, the diving bell—a kind of submerged breathing chamber—was already a familiar tool for exploring underwater wrecks. But it still had its flaws: it was clunky, unstable, and gave divers little control once they were lowered beneath the waves. That is, until Charles Spalding, an Edinburgh confectioner turned underwater innovator, decided to change that.

After suffering financial ruin when a ship carrying his goods sank, Spalding did what few would even dream of—he built his own diving apparatus to retrieve the cargo. His upgraded version included balance weights to steady the bell in turbulent water, a clever signal rope system for communicating with the crew above, and—finally—a window so divers could actually see what they were doing.

And yes, he even fashioned rope seats, which sounds simple, but was a big leap in comfort at the time.

Although Spalding never managed to recover his lost investment, his improvements were recognized by the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce, which awarded him funds for his work. Diving soon became more than a side project—it became his obsession.

Tragically, this same obsession claimed his life. In 1783, while descending to the wreck of the BelGioso in Dublin Bay, Charles Spalding never resurfaced.

7. The World’s First Military Submarine: A 1720 Marvel

Believe it or not, the world’s first military submarine was trialed way back in 1720! This isn’t a modern – day invention; it dates back centuries. Russian carpenter Yefim Nikonov, who had no formal engineering background, was the mastermind behind this ingenious creation.

Nikonov came up with the idea of a stealth vessel that could take on warships in an entirely new way. His submarine was armed with rocket missiles. Can you imagine that back then? He claimed in the specifications he submitted to Tsar Peter the Great that this vessel could “knock out a warship from below.” He was so confident that he said it could take out “at least ten or twenty” warships. And to prove his seriousness, he stated that if he was wrong, “he was ready to answer with his head.”

After 13 months of hard work, Nikonov launched a small prototype. It was a significant moment. In the Neva River, this prototype successfully dived and resurfaced. People must have been in awe of this strange new craft. However, there was a hitch. During a second trial, witnessed by the tsar himself, the sub failed to resurface. But instead of giving up on Nikonov, Peter the Great still allowed him to proceed with his project.

The finished vessel, initially called Model but misnamed Morel by a clerk, was an interesting sight. It measured six meters in length and two meters in height. It looked like a huge wooden barrel, equipped with iron hoops. And for an added touch of firepower, it had flamethrowers.

Powering this unique vessel were oarsmen. Each oarsman wore a diving suit designed by Nikonov himself. To make the Morel submerge, water was taken in through ten tin plates into leather bags lining the vessel. This process increased the weight, causing it to sink. When it was time to resurface, a copper piston pump was used to discharge the water.

Sadly, there were some issues. After diving to a depth of 3 – 4 meters, the sub was damaged when it scraped along the ground, tearing it open. Fortunately, the crew was rescued. Even after this set – back, the tsar remained keen on the project.

But fate took a cruel turn. When Peter the Great passed away, Nikonov lost his most powerful supporter. With a lack of funds, the next test in 1727 was doomed from the start. It failed, just as expected. And with that, the inventor was banished to Astrakhan. Submarines then disappeared from the scene for two long centuries.

6. Edmond Halley’s Diving Bell: The Comet Guy Who Revolutionized Deep-Sea Breathing

Yes, Edmond Halley is the same guy the comet’s named after—but his contributions went far beyond just tracking celestial fireballs. In 1691, Halley took his curiosity underwater and helped shape the future of deep-sea exploration with a radically improved diving bell.

While not the first to submerge in an air-filled chamber, Halley’s design changed the game by allowing divers to stay submerged for over 90 minutes at depths of 20 meters—an impressive feat for the 17th century. The secret? A clever air renewal system that pumped fresh air from the surface using weighted barrels equipped with valves. This kept the internal atmosphere breathable far longer than before.

But Halley wasn’t done experimenting. He also proposed a “mini bell” helmet, connected by a guts-made air hose to the main bell, so divers could leave the bell and still breathe underwater. His dream was to allow explorers to “goe out… and stay in the water as long as he pleased.” Basically, an early concept of scuba gear.

There was just one problem: water pressure. Halley underestimated its crushing effects. He reported agonizing ear pain during dives, describing it “as if a quill had been thrust into them.” Turns out, normal air at surface pressure doesn’t cut it below the waves. This realization eventually paved the way for pressurized suits—like John Lethbridge’s armored diving gear decades later.

5. The Margarita Diving Bell: Solving a 400-Year-Old Underwater Mystery

Long before Edmond Halley’s famous dive, there was the mysterious Margarita Diving Bell—a relic from the sunken Spanish galleon Santa Margarita, which went down off the Florida Keys in 1622. For decades, a copper saucer-shaped disc, measuring about 1.5 meters across and covered in rivets, sat in museums under a completely wrong assumption: experts believed it was used to cook fish aboard the ship.

But recent investigations revealed something far more fascinating—it was actually the cap of a diving bell, making it the oldest physical evidence of such a device ever discovered.

The full bell, commissioned in 1606 and used in a 1625 salvage mission, stood 1.2 meters tall, 0.9 meters wide, and weighed around 700 pounds. Divers would descend in this apparatus to recover treasure from the wreck. A breathing tube supplied fresh air from the surface, an advanced concept for the era.

Although much of the original bell was likely made of wood (and has not survived), the preserved copper top is now dubbed a “rare technological treasure” by historians. It proves that the Spanish were not only determined to recover their wealth but were also pioneers of early underwater engineering.

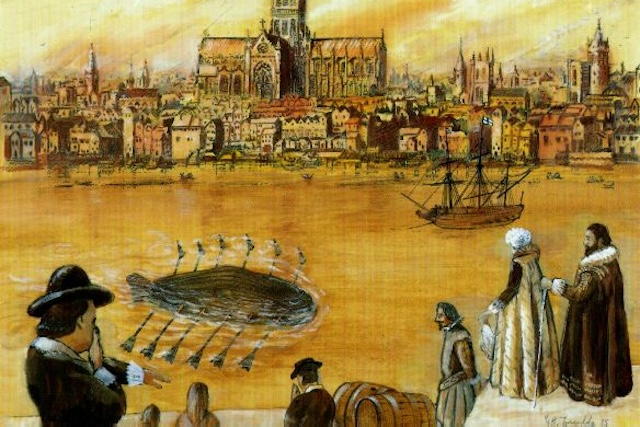

4. Drebbel’s Submarine: A Remarkable Feat in 1620

When we think about the history of submarines, one name that stands out is Dutch physician Cornelis Drebbel. He is widely credited with creating the world’s first navigable submarine, a truly remarkable achievement for its time.

Built in London specifically for King James I, the details of this submarine’s design have largely been lost to the annals of history. However, we do know a few tidbits that paint an intriguing picture. It seems that Drebbel’s creation was based on, or at least modified from, a regular rowing boat. This gives us an idea of how he might have started with a familiar concept and then transformed it into something revolutionary.

To make the boat more robust and capable of withstanding the underwater environment, it was reinforced with iron and covered with leather. This approach is somewhat reminiscent of Nikonov’s later design, showing that different inventors were exploring similar solutions to the challenges of underwater travel.

Just like the Morel, Drebbel’s submarine relied on oarsmen for propulsion. There were six oarsmen on each side of the vessel, and their oars poked out through watertight leather sleeves. This ingenious design not only allowed the oars to function effectively but also prevented water from seeping into the boat. Additionally, it had a rudder, which was crucial for steering the submarine and navigating through the water.

Now, let’s talk about its voyages. Between 1620 and 1624, Drebbel’s submarine had many successful journeys along the Thames. These weren’t just short jaunts; they were significant expeditions. The submarine was usually submerged to a depth of up to 15 feet. But how did they control the depth? Well, it involved an ingenious system of filling and emptying pigskin bladders with the surrounding water. Each bladder was connected to pipes that led out of the submarine, and there were also ropes attached to these systems to open and close them as needed.

One of the most impressive aspects of Drebbel’s submarine was its ability to stay underwater for extended periods. Thanks to air tubes that extended vertically out of the water, dives could last for hours at a time. Imagine being on a submarine during that era, with limited technology, yet being able to remain submerged for such lengths. And it’s not just speculation – apparently, the king himself was on one of these dives.

This achievement by Drebbel was a major milestone in the history of submarines. It showed that humans could design and operate a vessel that could safely and effectively explore the underwater world. It was a testament to the creativity and ingenuity of inventors like Drebbel, who dared to dream beyond the boundaries of what was known at the time.

3. William Bourne’s Submarine: The Forgotten Blueprint from 1578

Long before submarines became a naval reality, English mathematician William Bourne envisioned a vessel that could travel beneath the waves. In 1578, he published detailed plans for what might be the first ever design of a functional submarine in his book Inventions, or Devises—decades before Dutch engineer Cornelis Drebbel took the credit for building one.

Bourne’s concept was a rowboat enclosed in a watertight, leather-covered wooden frame, with oarsmen inside providing propulsion. Though there’s no record of it ever being built, the ingenuity behind the design is clear. It featured a compressible hull—allowing it to change buoyancy—and an understanding of water displacement far ahead of its time.

Despite having wealthy aristocratic patrons, including lords, earls, and even an admiral, Bourne passed away just four years later and never saw his vision realized—or defended. Drebbel’s later submarine in the early 1600s, often credited as the first, bears striking resemblance to Bourne’s earlier blueprints.

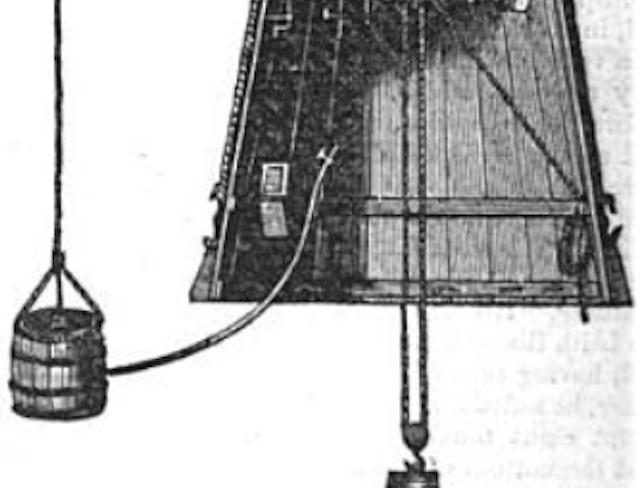

2. The Mysterious Lake Nemi Diving Bell of 1531

Long before modern scuba gear or submarines, divers exploring the depths of Lake Nemi, near Rome, may have used one of the most sophisticated early diving bells in recorded history. The mission? To investigate the sunken pleasure barges of Emperor Caligula, opulent floating palaces lost since the first century AD.

While an earlier recovery attempt in 1446 involved Genovese seamen free-diving to tie ropes around the massive wrecks—only to break off chunks of wood—the 1531 expedition took a different approach. Funded by a cardinal, this second effort made use of a custom-built diving bell. The technology was so advanced for its time that it remains a historical mystery.

According to accounts, the bell had a way to expel exhaled air, allowing for dives of up to two hours. Divers didn’t surface due to lack of oxygen, but rather because of cold and physical fatigue—a remarkable claim considering that even 18th-century bells struggled to offer such longevity. However, the mechanism behind this capability was deliberately kept secret by its inventor, and no detailed schematics survive.

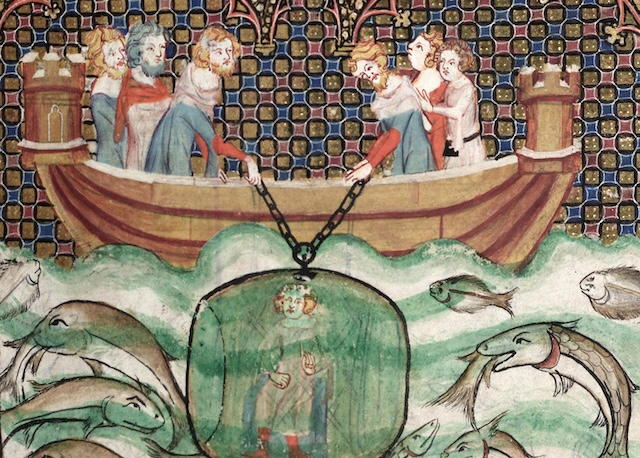

1. The Mysterious Bathysphere of 332 BC: Alexander’s Undersea Venture

When we delve into the annals of history, the year 332 BC presents us with a fascinating tale related to undersea exploration – the story of the Bathysphere. This account is intertwined with the legendary military campaign of Alexander the Great during the Siege of Tyre.

It is said that for the Siege of Tyre, Alexander the Great had a rather remarkable contraption built – “a very fine barrel made entirely of white glass.” The purpose of this unique creation was to scout out the undersea defenses of the city. Imagine the scene: after this unusual vessel was towed out to the vast expanse of the sea, Alexander himself, accompanied by two of his companions, bravely climbed inside. Then, they were lowered into the depths of the water.

Aristotle, that great philosopher and chronicler of his time, provides us with an account of what happened next. According to him, as they were in the submersible, they were stunned by the bright lights emanating from within the bathysphere. What’s more, Alexander’s reaction was quite extraordinary. He was moved, much like astronauts are when they witness the vastness of space, but not with a sense of wonder or awe. Instead, he was filled with melancholy. He later uttered these profound words: “the world is damned and lost. The large and powerful fish devour the small fry.” This shows how this undersea experience had a deep emotional impact on him.

However, the exact nature of this vessel remains a mystery. It’s not entirely clear whether it was indeed a diving bell. A later account offers a different description, stating that it was a “glass case, reinforced by metal bands.” And to lower it, they used “a chain over 600 feet long.” Given the nature of the accounts and the time period, it’s indeed challenging to separate fact from fiction when it comes to Alexander the Great and his exploits.

But here’s an interesting point. Diving bells were not entirely unknown in the classical world. Aristotle, in his Problemata, describes a method that was used by sponge divers. He talks about a “kettle” filled with air that was lowered down to them. This was done to assist the divers in staying underwater for a longer duration. To ensure that the air didn’t escape and water didn’t enter, “the kettle was forcibily kept upright in its descent.”

Before the concept of the diving bell became more widespread, undersea operations were far more rudimentary. Divers had to rely on some basic yet dangerous techniques. They would fill their mouths and ear canals with oil. Then, with the aid of rocks, they would sink down into the water. They had to do as much work as they could before someone hauled them back up to the surface with a rope. The other options for getting a glimpse of the underwater world were free-diving and using hollowed-out reeds for snorkeling. These methods, while functional to some extent, were extremely limited in what they could achieve.

The story of the Bathysphere in 332 BC, whether it was a diving bell or not, serves as a testament to the human spirit of exploration. Even in ancient times, people were curious about the unknown depths of the sea, and they were willing to take risks to satisfy that curiosity. It’s a story that continues to captivate us and makes us wonder what other secrets the past might hold about undersea exploration.